Deciding isn't enough

This is a chunky read, but you should find it interesting if:

- you are sick of people telling you to just "decide" - like that's all there is

- you've been as perplexed as I have about why deciding something doesn't guarantee we'll do it

OK. Here we go.

This all started with tweet from For The Interested. It linked to a 2016 article by Josh Spector which talked about the role of intention in productivity. To master our schedules and inboxes, Josh suggests, we need to “decide what matters; decide when YOU want to do things; and decide what to let slide”.

This tweet sparked a couple of thoughts.

It’s the deciding that’s the hard part

First, the problem is always that word, “decide”, isn’t it? Life would be simple if decisions were easy. But it’s the decision that’s the hard thing - the thing we put off, ruminate on, wake up thinking about.

Take “decide what matters”, for example. Where to begin? Josh’s advice, “decide what we care about - what’s most important, what do we value, and what impact do we want our effort to create?”

Easier said than done, I’d suggest. Of course it’s easy once it’s decided, but deciding it is the agony.

The decision isn’t the action to make it happen

The second is something I write about in my book, The How of Habits. It’s an old riddle you might have heard?

There are 10 frogs sitting on a log and 9 decide to jump off.

How many frogs are left on the log?

10, because deciding and doing are not the same thing.

It’s this gap between decision and action that I find most interesting. Does making a decision guarantee you’ll follow through?

No. So is it a 70% conversion? 90%?

Here’s what I’ve nutted out.

I call it the “Decision-Action Conversion (DAC)”. There are two dimensions to DAC.

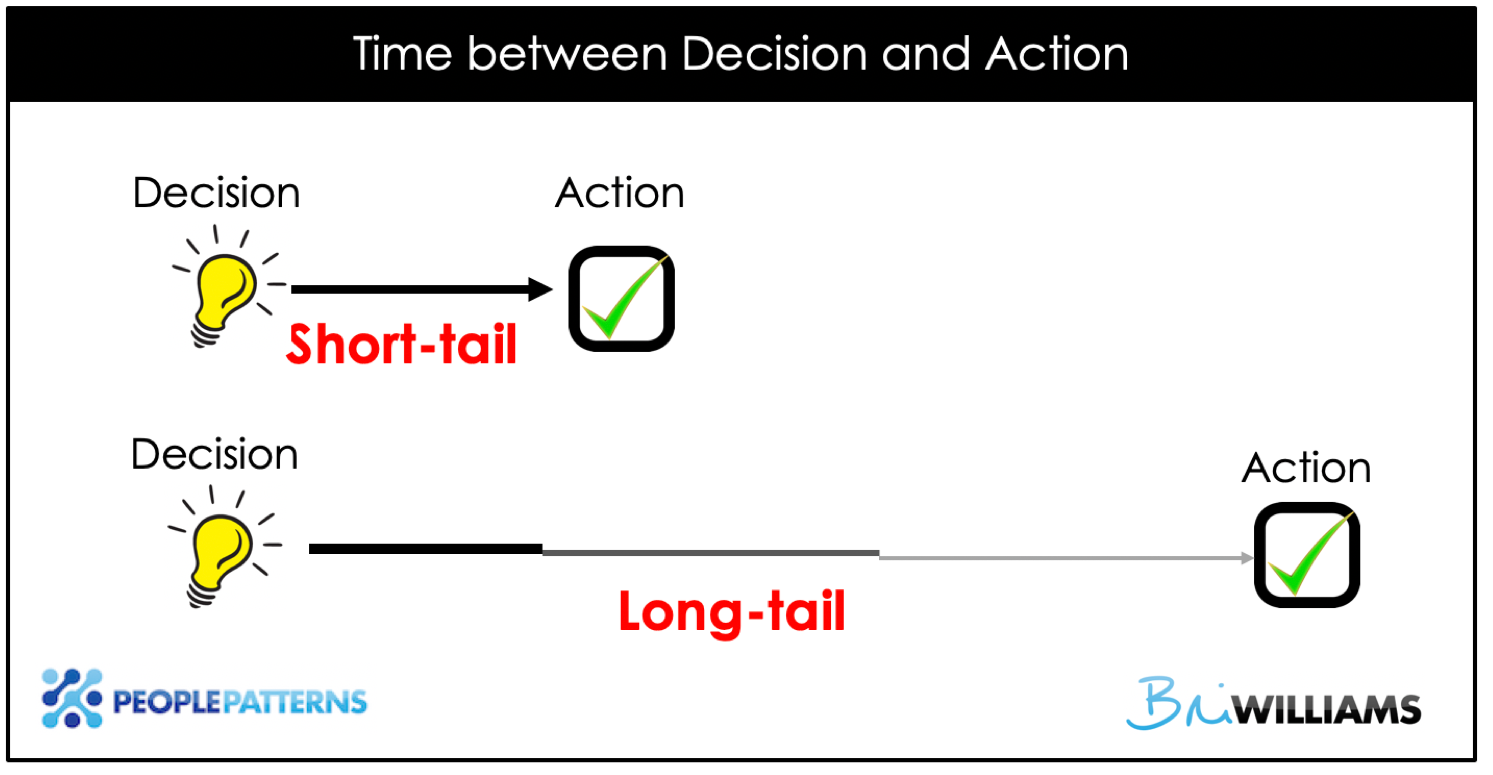

Time between Decision and Action

In some cases, there is only a short gap between making the decision and acting on it. Finding snacks in the pantry is probably the best example - the time between me deciding to eat a cookie and gobbling it down is usually (embarrassingly) short.

This is what I call a “short-tail DAC”. On a website, the time between deciding to click a button and actually doing is a short-tail DAC.

A “long-tail DAC” means there is a large gap between decision and action. I decide to change jobs, for example, but then do nothing about it for another year.

The longer the elapse between decision and action, the greater the risk of interference, of second-guessing and excusing inaction. Intensity has a chance to dip, allowing motivation to fall away.

Degree of Decision-Action boundedness

There’s a second dimension at play, too. How loosely or tightly bound you are to the decision?

By that I mean, how easy is it to get out of the action? What’s your accountability to yourself and others?

If you are tightly bound, the decision is a fait accompli. Making the decision is as good as acting on it.

When a judge makes the decision to jail someone, for example, there are all sorts of controls and mechanisms that mean that they have no choice but to see it through. This is like driving on a freeway without any exits; you are committed to the action even if you want to get off.

If you are loosely bound, the decision is more malleable. It becomes a suggestion rather than mandate; an idea rather than commitment. Here you can pull off the highway at anytime and grab a burger and chips.

Relationship between boundedness and time

Putting it all together, the degree of bounded-ness and the time between decision and action mean we can develop strategies to change the rate of decision-to-action conversion.

For the rest of this explanation I am going to assume you want the decision to lead to action. There are many cases however, where you will want to prevent the action from occurring (e.g. thwarting the decision to binge on chocolate, or a customer’s decision to cancel their subscription with you).

1. Lowest odds of Decision-Action Conversion

The lowest odds of a decision resulting in an action is when you combine long-tail and loosely bound conditions.

This is a decision where I have no accountability (to myself or others) and there is a delay between when I make the decision and when I have to do something about it.

There’s a high risk of failure because it’s easy to let myself off the hook and the intensity has dropped.

To improve your odds of success:

- Increase the accountability systems and structures and/or

- Reduce the time between the decision and first action

2. Highest odds of Decision-Action Conversion

The highest odds of seeing a decision turn into action is the combination of short-tail and tightly bound conditions.

Here I have systems or structures to hold me to my decision, and no time to second-guess and weasel out of it.

3. Loosely bound, short-tail

Where you have limited accountability but only a short elapse between decision and action, your success will rely on the degree of automaticity. The more intuitive and easy the action, the greater the likelihood it will occur.

This is the domain of default bias, where the path of least resistance makes or breaks conversion.

To improve your odds of success:

- Ensure the default is the desired action

4. Tightly bound, long-tail

In situations where there is a high degree of systems and structures in place, but a significant gap between the decision and action, success depends on how well those guard rails shepherd the decision through to action.

To me this is like a ten pin bowling alley where gutter guards are in position - the ball can’t help but knock down the pins because there is nowhere else to go.

If you remove accountability, you are at significant risk of the decision not resulting in an action.

To improve your odds of success:

- Reduce the elapse between decision and action and/or

- Ensure the systems and structures support the entire time between decision and action

I know this was a long-read but this gap between decision and action I think is really important.

Interestingly, while I hadn’t meant it to be, this feels like a companion to my piece on the overuse of “inform”. Both “informing” and “deciding” seem undercooked as objectives, like the behavioural job hasn’t been done.

The more I work and study the nuance of behavioural influence, I realise the gold is in the cracks. Only by delving into these grey areas can we become more effective in getting ourselves and others to take action.